English

English

French

French

Knowledge of asthma of parents with asthmatic children at a hospital in Ho Chi Minh City - Vietnam

Connaissance de l'asthme des parents d'enfants asthmatiques dans un hôpital à Ho Chi Minh Ville - Vietnam

Nguyen-Nhu Vinh1,2, Duong-Quy Sy2,3 , Tran Duc Tuyen1, Huynh Trung Son1, Nguyen Nhat Quynh1, Pham-Le An1

1: University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City 0028, Vietnam

2: Department of Respiratory Functional Exploration, University Medical Center, University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City 0028, Vietnam

3: Bio-Medical Research Center, Lam Dong Medical College, Dalat City 0263, Vietnam

Corresponding author:

Pham-Le An. University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Ho Chi Minh City 0028, Vietnam

E-mail: anpham_vn@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction. In Vietnam the majority of young asthmatics have a poor control of their condition. In addition to factors related to the healthcare system and/or healthcare providers, parents’ knowledge of asthma and its management has also contributed to this situation. We assessed the understanding of caregivers whose children suffering from asthma at a pediatric respiratory ward in Ho Chi Minh City. Methods. A cross-sectional study with convenience sampling was conducted among parents with asthmatic children using questionnaires administered during a face-to-face interview. After being validated, the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ) was applied to determine the level of asthma knowledge in the parents. Sociodemographic factors were collected and their relationship to the level of knowledge was analysed. Results. 131 parents with children participated in the study. The mean age of parents was 35.56±5.6 and that of their children was 5.6±2.8. The average score of level of knowledge (the NAKQ score) was 19.8±2.6. There was a relationship between education, occupation, economic status, the presence of other asthmatic children in the family and the parental knowledge of asthma. Conclusions. The level of asthma knowledge among parents who participated in the study was low and substantially correlated with the level of asthma control. Greater efforts are needed to improve the knowledge to enhance asthma management in Vietnam.

KEYWORDS: Asthma; Knowledge; Children; NAKQ; Vietnam.

RÉSUMÉ

Introduction. Au Vietnam la majorité des jeunes asthmatiques ont un mauvais contrôle de leur condition. En plus des facteurs liés au système de santé et/ou aux fournisseurs de soins de santé, la connaissance des parents de l'asthme et de sa prise en charge a également contribué à cette situation. Nous avons évalué la compréhension des soignants dont les enfants souffrent d'asthme dans un service respiratoire pédiatrique à Ho Chi Minh-Ville. Méthodes. Une étude transversale avec échantillonnage de convenance a été menée auprès de parents d'enfants asthmatiques à l'aide de questionnaires administrés lors d'un entretien en face-à-face. Après avoir été validé, le Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAKQ) a été appliqué pour déterminer le niveau de connaissance de l'asthme chez les parents. Les facteurs sociodémographiques ont été recueillis et leur relation avec le niveau de connaissance a été analysée. Résultats. 131 parents avec enfants ont participé à l'étude. L'âge moyen des parents était de 35,56±5,6 et celui de leurs enfants de 5,6±2,8. Le score moyen du niveau de connaissance (le score NAKQ) était de 19,8±2,6. Il y avait une relation entre l'éducation, la profession, le statut économique, la présence d'autres enfants asthmatiques dans la famille et la connaissance parentale de l'asthme. Conclusions. Le niveau de connaissance de l'asthme chez les parents qui ont participé à l'étude était faible et substantiellement corrélé avec le niveau de contrôle de l'asthme. Des efforts accrus sont nécessaires pour améliorer les connaissances afin d'améliorer la gestion de l'asthme au Vietnam.

MOTS CLÉS: Asthme; Connaissance; Enfants; NAKQ ; Vietnam.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a major chronic disease among children and adults and remains a significant health problem in Vietnam [1-3]. The prevalence of asthma in Vietnam among adults aged 21-70 years has been estimated at 3.9-5.6% [4]. In Ho Chi Minh city (where this study was conducted) the prevalence of ‘ever asthma’ among 6-7-year-olds was 10.9% and that of wheezing in children aged 13-14 years was 29.5%, the highest in the Asian-Pacific region [5]..

Because asthma cannot be cured, the aim of asthma management is to control the disease and allow patients to lead a normal and healthy life.6 To achieve this, patients need to use medications correctly and maintain control for a considerable period of time. This might be achieved if patients or caregivers of asthmatic children receive adequate guidance on how to use medications and receive sufficient knowledge about the disease [6]. They should also be aware that adhering to the treatment plan is the mainstay of asthma management [6]. In addition, asthma is a variable disease (i.e. it can change over time), implying that even when a patient has achieved a well-controlled asthma level, an asthma exacerbation can still occur. Deaths from asthma 85% can be avoided if detected promptly and treated properly [6].

Inadequate asthma control increases the risk of hospitalization, resulting increased medical costsand diminished quality of life for children and caregivers, and imposing a heavy burden on the national health system.7 Ineffective asthma control involves improper use of the drug, non-compliance with treatment as directed by the doctors due to the existence of mistakes in understanding the mechanism of pathogeneses, the benefits of exercise, the reason for limiting exposure to risk factors, the importance of the use of preventive drugs, side effects of the drug is also a barrier to controlling asthma attacks [7,8].

Nowadays, despite many advances in diagnosis and treatment, the prevalence of controlled asthma is still low worldwide, including Vietnam. It has been reported that, particularly, less than 1% of patients in Vietnam had asthma that was well managed [9]. Besides issues related to the healthcare system (e.g. unavailability of controllers,10 unaffordability for some patients, [1,2,11-13], physicians (e.g. incorrect diagnosis, lack of knowledge on asthma management, insufficient time or unwillingness to discuss matters with patients [14,15] and patients (e.g. low level of treatment adherence), the insufficient understanding of patients and caregivers about the disease is an important factor contributing to the low level of asthma control [16].

Therefore, patients and caregivers should be informed about how to manage their children’s disease and how to get support from healthcare providers when the

child had an asthma exacerbation [17]. A previous study in Vietnam involving the caregivers of 5-year-olds showed that 54.6% of caregivers did not know how to handle asthma attacks and 42.2% were unable to identify the right quick-relief medications [18].

The patient’s and caregiver’s general knowledge of asthma may comprise knowledge on the pathophysiology of asthma, the purpose of different types of medication, the management of environmental asthma triggers, the identification and management of asthma exacerbations, and the use of inhalers [13,19]. In many countries, although levels of asthma self-management are low (regarding both knowledge and practice of asthma patients), the situation could be improved by means of education [11,20-22] and better asthma control, fewer exacerbations, fewer hospital admissions and a higher quality of life could be achieved with increased asthma knowledge [6,23,24 ].

Currently, data are lacking regarding knowledge of asthma of caregivers of asthmatic children in Vietnam. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the degree of asthma knowledge of caregivers of asthmatic children, as well as the relationship between this knowledge and other participants’ demographic characteristics.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This was a prospective cross-sectional study. Eligible participants were parents of ambulatory patients (recruited between March 2020 and May 2020) at the Asthma clinic, Children's Hospital 2, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Ethical approval

Participation was voluntary. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study. Data were analyzed anonymously. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Parents i) who were aged ≥ 18 years, ii) whose children had been diagnosed with asthma at least 6 months and were followed-up at this clinic, iii) and who had sufficient command of the Vietnamese language to respond to questionnaires were eligible for inclusion in this study.

Participants were excluded if they met any of the following exclusion criteria: i) cognitive impairment and inability to communicate verbally; ii) refusal to participate in the study; or iii) having children with other respiratory diseases comorbidity with asthma.

Sample size and sampling technique

Based on the literature, it was assumed that the mean and variance of the asthma knowledge based on NAKQ score is 18.5 ± 3.7 (σ = 3.7) [25], with maximum error deemed acceptable d=0.6475 (d = 0.035 × 18.5 = 0.6475 - expected deviation of 3.5% from the mean), error type I α=0.05 and normal variable z=1.96 (95% reliability of the estimates).

The sample size required was 126 patients based on the formula n = Z2(1-α/2) × σ2/d2. A convenience method of sampling was adopted.

Data collection

Data were collected via a face-to-face interview using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire comprised the following sections:

iii) The Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (NAQK): The NAKQ has 31 items to assess the knowledge of asthma symptoms, triggers, and treatment, consisting of 25 true/false questions and six open-ended questions [26].

Each correct answer was worth 1 point and the incorrect was worth 0 point. The minimum and maximum score were 0 and 31 respectively, with a higher score indicating greater knowledge.

In addition, the questionnaire is given a cutting point of ≥21 points (equal to 65% correct answers) for satisfactory levels (suitable) and <21 for unsatisfactory levels (inappropriate) [27].

The open-ended questions of the questionnaire were scored by investigators who adhered stringently to the scoring guidelines.

The text of the first question implies that the answer must include all three main asthma symptoms, so answers have only been rated as correct when all three were enumerated.

The answer to question 6 has been rated as correct if the respondent named at least one of the three triggers that are established as possible answers.

Questions 10, 11, 21, and 23 have been rated as correct when the respondent has given at least two of the answers that the questionnaire offers as possible answers, as indicated by the scoring rules of the original questionnaire [26].

The NAQK was translated according to the WHO process of translation and adaptation of instruments.

This process involved the following steps: forward translation, expert panel back-translation, pre-testing and cognitive interviewing, and the final version [28].

A pilot study was conducted to test the questionnaire with a group of 25 parents to verify the feasibility and acceptability of the questionnaire and to establish the time frame for data collection.

Minor observations were suggested and adopted in the final version. The pilot sample was not included in the final analysis.

Data analysis

Data were processed with Excel 2016 software and analyzed using STATA 13.0 and NVIVO10 software. Quantitative variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD) for normal distribution variables and as medians and interquartile ranges for non-normal distribution variables.

Student’s t-test was used to compare the means of two groups and one-way ANOVA to compare the means of multiple groups. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General characteristics of the research population

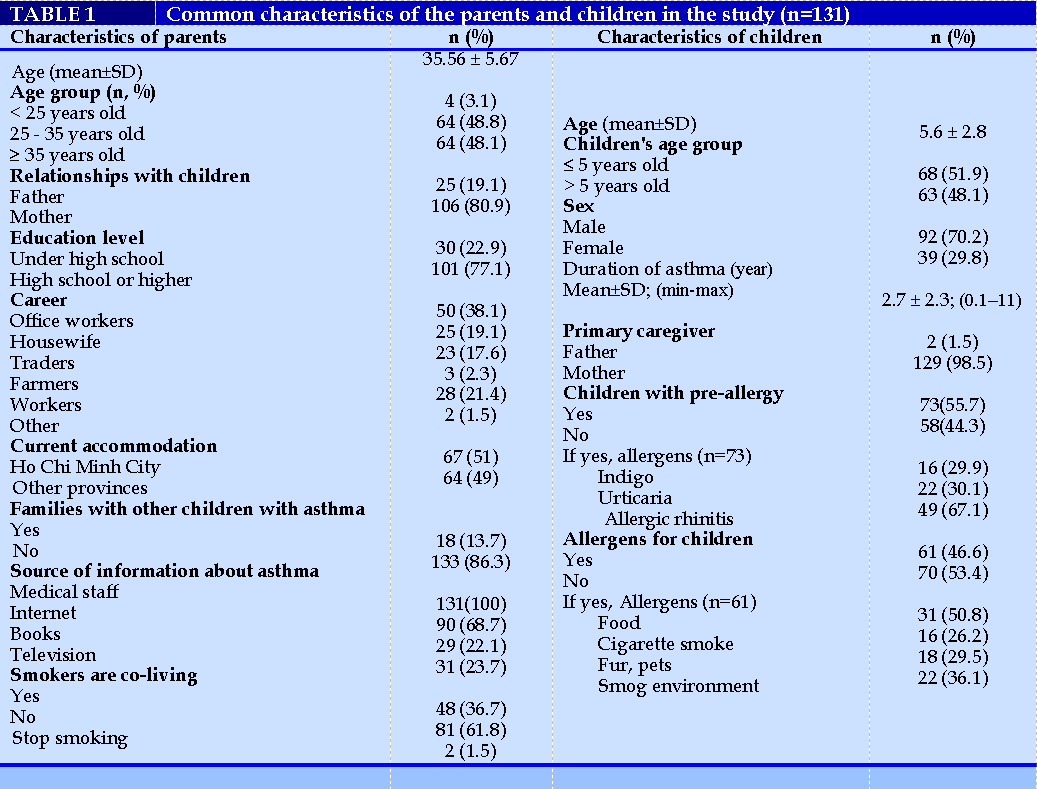

Of the 150 parents (each for 1 asthmatic patient) invited to participate, 140 (93%) responded and 131 (87%) responses were satisfied to be analyzed. The mean age of participating parents was 36 (range 22-58) years and mothers comprised 81% of participants.

Most primary caregivers were mothers, accounting for 98.5%. The mean age of asthmatic children wass 6 years (range 2-14) and male asthmatics comprised 70%. Additional characteristics are presented in Table 1. Nearly 70% of parents learned asthma information on the internet; 100% of parents got information from medical staff but 30% received information only from this source without looking for other sources.

Asthma knowledge

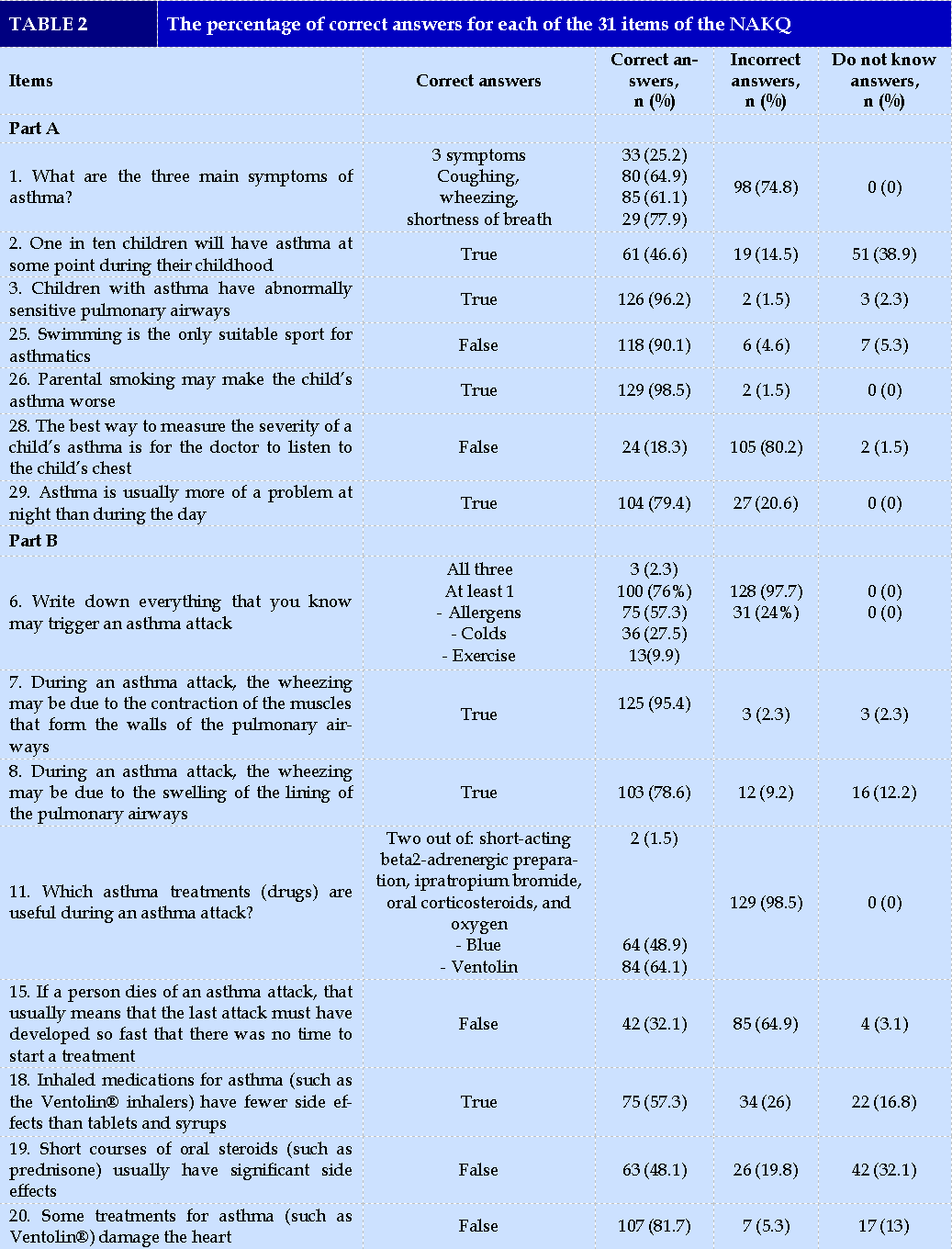

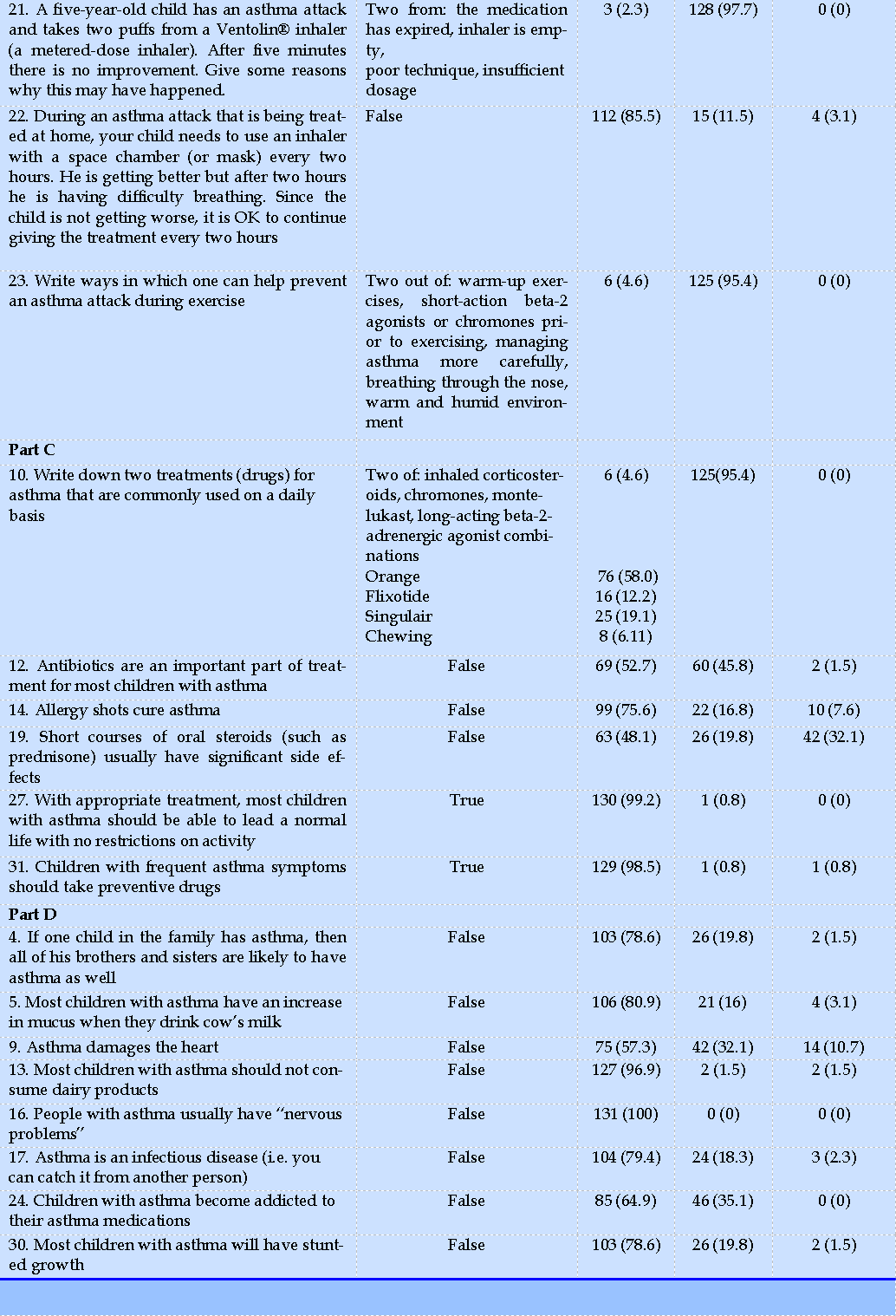

The results showed that of the 131 participants, 31.1% answered correctly ≥ 65% of the question sets (NKAQ ≥ 21). The knowledge score of parents of children with asthma was 19.1 ± 2.5. Figure 1 details the correct answers and percentage of correct, incorrect and unkown answers for 31 NAKQ questions.

Table 2, Table 2.2 shows the percentage of correct, incorrect and unknown answers of the NAKQ which was grouped into 4 parts: part A is general knowledge of asthma (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q25, Q26, Q28, Q29), part B is knowledge related to exacerbations (Q6, Q7, Q8, Q11, Q15, Q18, Q19, Q20, Q21, Q22, Q23), part C is knowledge of asthma treatment (Q10, Q12, Q14, Q19, Q27, Q31) and part D is false beliefs about asthma (Q4, Q5, Q9, Q13, Q16, Q17, Q24, Q30).

From the above data, a detailed analysis of parents’ asthma knowledge is described as the following:

General asthma knowledge (part A)

In these seven questions, 85% of participants that gave ≥ 65% correct answers were considered as adequate knowledge for this section.

The majority of parents (61.2%-77.9%) knew each of three common symptoms of asthma (coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath) but only 25% of them knew all three (Q1).

Nearly half of parents were aware of the prevalence of asthma in children and 96% of participants knew that asthmatic children have abnormally sensitive pulmonary airways.

Almost all participants agreed that smoking worsens their children’s asthma and that asthma usually happens at night. However, the majority of parents (80.2%) wrongly thought that the severity of asthma is assessed by hearing the lungs of the child by doctors.

Knowledge related to exacerbations (part B)

For this part, only 7.6% of participating parents answered correctly ≥ 65% of the 11 questions, which is the lowest percentage when compared to other sections.

In terms of acute asthma attack knowledge, almost all parents (97.7%) did not identify all the three main triggers (colds, allergens, and exercise), but allergens were recognized by 57.3% of participants.

There are 95.4% and 78.6% of respondents knew that contraction of the muscle and swelling of the lining of the airways, respectively, happens during an asthma attack.

64.9% disagreed that the most recent attack is not treatable. Most of participants knew Ventolin® as rescuers (64.1%) but only 1.5% were able to name at least 2 drugs that are useful during an asthma attack.

When comparing side effects between inhalers and oral steroids in question 18 and question 19, about half of respondents (48.1% - 67.3%) gave correct answers. 81.7% stated that Ventolin® did not damage the heart.

Regarding acute asthma attacks that do not improve after using Ventoline®, only 2.3% could identify at least two reasons.

The same percentage (4.6%) named correctly at least two ways to prevent an asthma exacerbation during exercise. Additionally, 85.5% knew that continuously

using inhaler rescuers at home for children who got breathless - after two hours of improvement from the first use – is incorrect.

Knowledge related to maintenance treatment (part C)

In terms of asthma treatment, 65% of respondents had ≥ 65% correct answers. However, only 4.6% wrote the names of two daily asthma medications, while 58% knew that orange medicine is a maintenance drug. Most parents remembered the color and usage of the drug.

About half of the participants knew that antibiotics are not an important treatment

(52.7%) and that a short course of oral steroids does not have significant side effects (48.1%).

75.6% were aware that allergy shots cannot cure asthma. Almost all respondents knew that with appropriate treatment, most children with asthma should be able to lead a normal life with no restrictions on activity (99.2%) and children with frequent asthma symptoms should take preventive drugs (98.5%).

Knowledge related to false beliefs (part D)

Regarding false beliefs about asthma, 85.5% of parents had suitable knowledge, whereas 19.8% believed that if one child in the family has asthma, then his siblings are also likely to suffer from asthma.

Besides, 16% thought that drinking milk can increase mucus production in asthmatic children and 32.1% stated that asthma can raise the heart disease risk.

On the other hand, 1.5% believed that most asthmatic children should not consume dairy products, and while 0% thought that asthmatics have nervous problems, 18.3% believed that asthma is an infectious disease.

Finally, 35.1% thought that asthmatics are addicted to asthma medications and 19.8% stated that most asthmatic children would have stunted growth.

Relationships between asthma knowledge and characteristics of parents

There is no relationship between knowledge of asthma and characteristics of gender, ethnicity, age group, hatching, smokers living with children, pre-allergic diseases.

Meanwhile, there are statistically significant differences between asthma knowledge and education, occupation, economic status, and the presence of other asthmatic children in the family (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, 131 parents of asthmatic children in an outpatient department of children hospital answered a face-to-face interview using NAKQ Vietnamese version. This version was translated according to WHO process with pilot study with 25 parents. The result of the present study shows that the mean NAKQ score of participating parents was 19.1 (with a maximum score is 31) and only 31.1% mothers/fathers had adequate knowledge about asthma (NAKQ score ≥21), which is similar to that of Roncada study in Brasil (30.5%) [27].

The mean NAKQ score of our study (19.1) is comparable to that of a Brazil’s study (19.3)33 and is higher than that of Malaysia (15.5)32 and studies using Spanish version (15.7 - 18.5) [29-31].

In terms of 4 main domains of this survey, general knowledge of asthma, knowledge related to exacerbations, knowledge of asthma maintenance treatment and knowledge related to false beliefs about asthma, the percentage of adequate knowledge (the cutoff of 65% correct answers) in each domain is 85%, 7.6%, 65% and 85.5% respectively. This finding means that although preventing, recognizing and reacting to asthma exacerbation is very important, most Vietnamese parents in our study population do not know much about asthma attacks. About 80% of parents were unable to recognize the main causes of asthma exacerbations, according to a Spanish study of 95 parents of children with asthma who were hospitalized in the emergency room.31 Lack of knowledge of asthma exacerbation has been happening worldwide when assessed by NAKQ [32.34]. Therefore, future asthma education for patients and caregivers should place a significant emphasis on asthma exacerbations.

However, with all open-ended questions in which the answers are considered as correct if the respondents wrote at least 2 things right for each question (Q1, Q10, Q11, Q21 and Q23), the proportion of correct answers is very low with 25.2%, 4.6%, 1.5%, 2.3% and 4.6% respectively. This patternwas also observed in other studies, such as the study of Cabelloa MTL et al, in which the correct response rates for questions Q1, Q10, Q11, Q21 and Q23 were 21.5%, 43%, 39.2%, 7% and 4.9%, respectively [34]. The rate of correct answers for Q10 (4.6%) and Q11 (1.5%) in Vietnam is extremely low due to the fact that the names of asthma medications are in English, which is difficult for Vietnamese people to remember. These figures are lower than those in an Asian country (Malaysia) (10.4% and 17.9%, respectively, for Q10 and Q11) where English is commonly used in the general population [32]. In addition, it is more difficult for patients/parents to respond to open-ended questions than choosing from a variety of given options, confirmed by Bruzzese, J. M. [35]

Question 6 is the only open-ended question for which the correct answer was determined if respondents named at least 1 right trigger. With this option, the rate of the correct answer is high (76%) compared to other open-ended questions. However, in the present study, 2.3% of respondents listed all three main asthma attack triggers (colds, allergens and exercise), which is similar to the result of Cabelloa MTL study in Spain (4.4%) but lower than that of Maylaysia (13.4%) [32,34]..

In terms of general asthma knowledge, our results showed that the percenatge of parents who knew the three main symptoms of asthma (cough, wheezing and shortness of breath) is comparable to findings of many previous studies (20-43%) [33,34].. Particularly,

the correct answer rate was less than 7% for questions about asthma prevention during exercise, 2.2-4.4% for correctly naming three groups of asthma causes, and 2.3-4.4% for the causes of improper use of the drug use.

Anxiety regarding the side effects of oral steroid pills is a common parental problem [36]. Study by author Jhao Z (2013) in China reported that 67.32% of parents worry about the adverse effects of corticosteroid drugs that slow a child’s growth [37].

However, in our study 32% of parents were unaware of this drug, showing that young parents relied on the provision of a doctor's medicationand passively learned the effects of the drug their child used. Another interesting point is that about 35% of parents in our study thought Ventolin was harmful to the heart.

This may be explained by the side effects of Ventolin, which increase the child's heart rate after use. Finally, 43% of participants believed that asthmatic children will suffer from stunted growth As it can affect the physical development of a child if asthma is not treated properly, leading to malnutrition and chest deformity. Strengths and limitations.

One of the strengths of this study is that the NAKQ we adapted was translated into Vietnamese in accordance with social and culture context, taking into account the accuracy, readability and consistency. Besides, information omissions and selection bias were also reduced as we collected data via face-to-face interviews with a structural questionnaire. However, as the sampling period coincided with the beginning of the quarantine period for COVID-19 in Vietnam, the sample may not be representative of the population. Further studies, which take this issue into account, will need to be undertaken.

CONCLUSIONS

The knowledge score assessed by the NAKQ is 19.1 ± 2.5, indicating that parents with children with asthma among our study population have incomplete asthma knowledge, particularly in terms of preventive measures when exercising, the main symptoms, and side effects of the drug. Future health education and communication programs should focus on these issues.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Non.

REFERENCE

| 1. Nguyen TT, Nguyen NB. Economic Burden of Asthma in Vietnam: An Analysis from Patients' Perspective. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2014;17(7):A627. |

| 2. Nguyen NBT, Nguyen TTT. Incidence-Based Cost of Asthma in Vietnam. Value in Health. 2014;17(7):A777-A778. |

| 3. Asthma in Vietnam. Statistics on Overall Impact and Specific Effect on Demographic Groups. Available from http://global-disease-burden.healthgrove.com/l/48342/Asthma-in-Vietnam. [Last accessed on September 5, 2017]. |

| 4. Lam HT, Ronmark E, Tu'o'ng NV, Ekerljung L, Chuc NT, Lundback B. Increase in asthma and a high prevalence of bronchitis: results from a population study among adults in urban and rural Vietnam. Respir Med. 2011;105(2):177-185. |

| 5. Lai CK, Beasley R, Crane J, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax. 2009;64(6):476-483. |

| 6. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2017; http://ginasthma.org/2017-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 01/08/2017. |

| 7. Murua JK, Molina JV, Crespo MP, et al. La educación terapéutica en el asma. Paper presented at: Anales de Pediatría2007. |

| 8. Becker Allan, Bérubé Denis, Chad Zave, et al. Canadian pediatric asthma consensus guidelines, 2003 (updated to December 2004): introduction. Cmaj. 2005;173(6 ):pp. 12-14. |

| 9. Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, et al. Asthma control in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2):263-268. |

| 10. The Global Asthma Report 2011. Paris, France: The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011. |

| 11. Ait-Khaled N, Auregan G, Bencharif N, et al. Affordability of inhaled corticosteroids as a potential barrier to treatment of asthma in some developing countries. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2000;4(3):268-271. |

| 12. Nguyen AT, Knight R, Mant A, Cao QM, M. A. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in Vietnam. . Southern Med Review. 2009;2(2):2-9. |

| 13. Lai CKW, Kim YY, Kuo SH, Spencer M, Williams AE. Cost of asthma in the Asia-Pacific region. European Respiratory Review. 2006;15(98):10-16. |

| 14. Gonzalez Barcala FJ, de la Fuente-Cid R, Alvarez-Gil R, Tafalla M, Nuevo J, Caamano-Isorna F. Factors associated with asthma control in primary care patients: the CHAS study. Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46(7):358-363. |

| 15. Haughney J, Price D, Kaplan A, et al. Achieving asthma control in practice: Understanding the reasons for poor control. Respiratory Medicine. 2008;102(12):1681-1693. |

| 16. Nguyen K, Zahran H, Shahed, Peng J, Boulay E. Journal of Asthma, Early Online. 2011:1-8. |

| 17. World health organization. asthma. 2013; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs307/en/. |

| 18. Le Ngoc Thu, Hong PTM. Results of asthma management in children five years and younger based on the guideline of Vietnam Ministry Of Health for asthma in 2016 at the Children Hospital 2. Ho Chi Minh City Journal of Medicine 2019;23(1):29-35. |

| 19. Schaffer SD, Yarandi HN. Measuring asthma self-management knowledge in adults. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2007;19(10):530-535. |

| 20. Prabhakaran L, Lim G, Abisheganaden J, Chee CB, Choo YM. Impact of an asthma education programme on patients' knowledge, inhaler technique and compliance to treatment. Singapore Med J. 2006;47(3):225-231. |

| 21. Manchana V, Mahal RK. Impact of Asthma Educational Intervention on Self-Care Management of Bronchial Asthma among Adult Asthmatics. Open Journal of Nursing. 2014;04(11):743-753. |

| 22. M.Varalakshmi, Mahal RK. Evaluating Asthma Knowledge among Patients with Bronchial asthma; A Cross sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Didactics. 2014;4(7):16-20. |

| 23. Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, et al. Health Services and Delivery Research. In: A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS - Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library Copyright (c) Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. ; 2014. |

| 24. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma: 2014 update. Thorax 2014;69(Suppl. 1): i1-i192. |

| 25. Cabelloa MTL, Oceja-Setienb E, Higueraa LG CM, Belmontea EP, I G-a. Assessment of parental asthma knowledge with the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Pediatría Atención Primaria. 2013;15(58):117-126. |

| 26. Fitzclarence CAB, Henry RL. Validation of an asthma knowledge questionnaire. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1990;26(4):200-204. |

| 27. Roncada C, Cardoso TA, Buganca BM, Bischoff LC, Soldera K, Pitrez PM. Levels of knowledge about asthma of parents of asthmatic children. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2018;16(2):eAO4204. |

| 28. WHO. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. available from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/. Last accessed September 12, 2017. |

| 29. Lopez-Silvarrey Varela A, Pertega Diaz S, Rueda Esteban S, Korta Murua J, Iglesias Lopez B, Martinez-Gimeno A. Validation of a questionnaire in Spanish on asthma knowledge in teachers. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(3):115-120. |

| 30. Cabello MT, Oceja-Setien E, Higuera LG, Cabero MJ, Belmonte EP, I. G-A. Assessment of parental asthma knowledge with the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Rev Pediatr 2013;15:117-126. |

| 31. García-Luzardo M, Aguilar-Fernández A, Rodríguez-Calcines N, Pavlovic-Nesic SJApe. Conocimientos acerca del asma de los padres de niños asmáticos que acuden a un servicio de urgencias. 2012;70(5). |

| 32. Fadzil A, Norzila MZ. Parental asthma knowledge. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 2002;57(4):474-481. |

| 33. Roncada Cristian, Cardoso Thiago de Araujo, Bugança Bianca Martininghi, Bischoff Luísa Carolina, Soldera Karina, Pitrez Paulo Márcio. Levels of knowledge about asthma of parents of asthmatic children. Einstein (São Paulo). 2018;16(2). |

| 34. Cabelloa MTL, Oceja-Setienb E, LG H, Caberoa MJ, Belmontea EP, Gómez-acebo I. Assessment of parental asthma knowledge with the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Pediatría Atención Primaria. 2013;15(58):pp. 117-126. |

| 35. Bruzzese JM, Unikel LH, Evans D, Bornstein L, Surrence K, Mellins RB. Asthma knowledge and asthma management behavior in urban elementary school teachers. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2010;47(2):185-191. |

| 36. Koster ES, Wijga AH, Koppelman GH, et al. Uncontrolled asthma at age 8: the importance of parental perception towards medication. Pediatric allergy and immunology. 2011;22(5):pp. 462-468. |

| 37. Zhao Jing, Shen Kunling, Xiang Li, et al. The knowledge, attitudes and practices of parents of children with asthma in 29 cities of China: a multi-center study. BMC pediatrics. 2013;13(1):page 20. |

Figures - Tables

REFERENCE

| 1. Nguyen TT, Nguyen NB. Economic Burden of Asthma in Vietnam: An Analysis from Patients' Perspective. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2014;17(7):A627. |

| 2. Nguyen NBT, Nguyen TTT. Incidence-Based Cost of Asthma in Vietnam. Value in Health. 2014;17(7):A777-A778. |

| 3. Asthma in Vietnam. Statistics on Overall Impact and Specific Effect on Demographic Groups. Available from http://global-disease-burden.healthgrove.com/l/48342/Asthma-in-Vietnam. [Last accessed on September 5, 2017]. |

| 4. Lam HT, Ronmark E, Tu'o'ng NV, Ekerljung L, Chuc NT, Lundback B. Increase in asthma and a high prevalence of bronchitis: results from a population study among adults in urban and rural Vietnam. Respir Med. 2011;105(2):177-185. |

| 5. Lai CK, Beasley R, Crane J, et al. Global variation in the prevalence and severity of asthma symptoms: phase three of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC). Thorax. 2009;64(6):476-483. |

| 6. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2017; http://ginasthma.org/2017-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 01/08/2017. |

| 7. Murua JK, Molina JV, Crespo MP, et al. La educación terapéutica en el asma. Paper presented at: Anales de Pediatría2007. |

| 8. Becker Allan, Bérubé Denis, Chad Zave, et al. Canadian pediatric asthma consensus guidelines, 2003 (updated to December 2004): introduction. Cmaj. 2005;173(6 ):pp. 12-14. |

| 9. Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, et al. Asthma control in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111(2):263-268. |

| 10. The Global Asthma Report 2011. Paris, France: The International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011. |

| 11. Ait-Khaled N, Auregan G, Bencharif N, et al. Affordability of inhaled corticosteroids as a potential barrier to treatment of asthma in some developing countries. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2000;4(3):268-271. |

| 12. Nguyen AT, Knight R, Mant A, Cao QM, M. A. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in Vietnam. . Southern Med Review. 2009;2(2):2-9. |

| 13. Lai CKW, Kim YY, Kuo SH, Spencer M, Williams AE. Cost of asthma in the Asia-Pacific region. European Respiratory Review. 2006;15(98):10-16. |

| 14. Gonzalez Barcala FJ, de la Fuente-Cid R, Alvarez-Gil R, Tafalla M, Nuevo J, Caamano-Isorna F. Factors associated with asthma control in primary care patients: the CHAS study. Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46(7):358-363. |

| 15. Haughney J, Price D, Kaplan A, et al. Achieving asthma control in practice: Understanding the reasons for poor control. Respiratory Medicine. 2008;102(12):1681-1693. |

| 16. Nguyen K, Zahran H, Shahed, Peng J, Boulay E. Journal of Asthma, Early Online. 2011:1-8. |

| 17. World health organization. asthma. 2013; http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs307/en/. |

| 18. Le Ngoc Thu, Hong PTM. Results of asthma management in children five years and younger based on the guideline of Vietnam Ministry Of Health for asthma in 2016 at the Children Hospital 2. Ho Chi Minh City Journal of Medicine 2019;23(1):29-35. |

| 19. Schaffer SD, Yarandi HN. Measuring asthma self-management knowledge in adults. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2007;19(10):530-535. |

| 20. Prabhakaran L, Lim G, Abisheganaden J, Chee CB, Choo YM. Impact of an asthma education programme on patients' knowledge, inhaler technique and compliance to treatment. Singapore Med J. 2006;47(3):225-231. |

| 21. Manchana V, Mahal RK. Impact of Asthma Educational Intervention on Self-Care Management of Bronchial Asthma among Adult Asthmatics. Open Journal of Nursing. 2014;04(11):743-753. |

| 22. M.Varalakshmi, Mahal RK. Evaluating Asthma Knowledge among Patients with Bronchial asthma; A Cross sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Didactics. 2014;4(7):16-20. |

| 23. Taylor SJC, Pinnock H, Epiphaniou E, et al. Health Services and Delivery Research. In: A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS - Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library Copyright (c) Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. ; 2014. |

| 24. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network. British Guideline on the Management of Asthma: 2014 update. Thorax 2014;69(Suppl. 1): i1-i192. |

| 25. Cabelloa MTL, Oceja-Setienb E, Higueraa LG CM, Belmontea EP, I G-a. Assessment of parental asthma knowledge with the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Pediatría Atención Primaria. 2013;15(58):117-126. |

| 26. Fitzclarence CAB, Henry RL. Validation of an asthma knowledge questionnaire. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 1990;26(4):200-204. |

| 27. Roncada C, Cardoso TA, Buganca BM, Bischoff LC, Soldera K, Pitrez PM. Levels of knowledge about asthma of parents of asthmatic children. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2018;16(2):eAO4204. |

| 28. WHO. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. available from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/. Last accessed September 12, 2017. |

| 29. Lopez-Silvarrey Varela A, Pertega Diaz S, Rueda Esteban S, Korta Murua J, Iglesias Lopez B, Martinez-Gimeno A. Validation of a questionnaire in Spanish on asthma knowledge in teachers. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(3):115-120. |

| 30. Cabello MT, Oceja-Setien E, Higuera LG, Cabero MJ, Belmonte EP, I. G-A. Assessment of parental asthma knowledge with the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Rev Pediatr 2013;15:117-126. |

| 31. García-Luzardo M, Aguilar-Fernández A, Rodríguez-Calcines N, Pavlovic-Nesic SJApe. Conocimientos acerca del asma de los padres de niños asmáticos que acuden a un servicio de urgencias. 2012;70(5). |

| 32. Fadzil A, Norzila MZ. Parental asthma knowledge. The Medical journal of Malaysia. 2002;57(4):474-481. |

| 33. Roncada Cristian, Cardoso Thiago de Araujo, Bugança Bianca Martininghi, Bischoff Luísa Carolina, Soldera Karina, Pitrez Paulo Márcio. Levels of knowledge about asthma of parents of asthmatic children. Einstein (São Paulo). 2018;16(2). |

| 34. Cabelloa MTL, Oceja-Setienb E, LG H, Caberoa MJ, Belmontea EP, Gómez-acebo I. Assessment of parental asthma knowledge with the Newcastle Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire. Pediatría Atención Primaria. 2013;15(58):pp. 117-126. |

| 35. Bruzzese JM, Unikel LH, Evans D, Bornstein L, Surrence K, Mellins RB. Asthma knowledge and asthma management behavior in urban elementary school teachers. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2010;47(2):185-191. |

| 36. Koster ES, Wijga AH, Koppelman GH, et al. Uncontrolled asthma at age 8: the importance of parental perception towards medication. Pediatric allergy and immunology. 2011;22(5):pp. 462-468. |

| 37. Zhao Jing, Shen Kunling, Xiang Li, et al. The knowledge, attitudes and practices of parents of children with asthma in 29 cities of China: a multi-center study. BMC pediatrics. 2013;13(1):page 20. |

ARTICLE INFO DOI: 10.12699/jfvpulm.14.43.2023.1

Conflict of Interest

Non

Date of manuscript receiving

25/01/2023

Date of publication after correction

25/06/2023

Article citation

Nguyen-Nhu V, Duong-Quy S , Tran Duc T, Huynh Trung S, Nguyen Nhat Q, Pham-Le A. Knowledge of asthma of parents with asthmatic children at a hospital in Ho Chi Minh City - Vietnam. J Func Vent Pulm 2023;43(14):1-10